KMb Journal Club review by Anneliese Poetz, KT Manager, Kids Brain Health Network

Durlak, J. A. & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 327-350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

Milat A.J., Bauman, A., & Redman, S. (2015). Narrative review of models and success factors for scaling up public health interventions. Implementation Science, 10, 113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0301-6

Abstract (Durlak, 2008)

The first purpose of this review was to assess the impact of implementation on program outcomes, and the second purpose was to identify factors affecting the implementation process. Results from over quantitative 500 studies offered strong empirical support to the conclusion that the level of implementation affects the outcomes obtained in promotion and prevention programs. Findings from 81 additional reports indicate there are at least 23 contextual factors that influence implementation. The implementation process is affected by variables related to communities, providers and innovations, and aspects of the prevention delivery system (i.e., organizational functioning) and the prevention support system (i.e., training and technical assistance). The collection of implementation data is an essential feature of program evaluations, and more information is needed on which and how various factors influence implementation in different community settings.

Abstract (Milat, 2015)

Background: To maximise the impact of public health research, research interventions found to be effective in improving health need to be scaled up and delivered on a population-wide basis. Theoretical frameworks and approaches are useful for describing and understanding how effective interventions are scaled up from small trials into broader policy and practice and can be used as a tool to facilitate effective scale-up. The purpose of this literature review was to synthesise evidence on scaling up public health interventions into population-wide policy and practice, with a focus on the defining and describing frameworks, processes and methods of scaling up public health initiatives.

Methods: The review involved keyword searches of electronic databases including MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, EBM Reviews and Google Scholar between August and December 2013. Keywords included ‘scaling up’ and ‘scalability’, while the search terms ‘intervention research’, ‘translational research’, ‘research dissemination’, ‘health promotion’ and ‘public health’ were used to focus the search on public health approaches. Studies included in the review were published in English from January 1990 to December 2013 and described processes, theories or frameworks associated with scaling up public health and health promotion interventions.

Results: There is a growing body of literature describing frameworks for scaling health interventions, with the review identifying eight frameworks, the majority of which have an explicit focus on scaling up health action in low and middle income country contexts. Key success factors for scaling up included the importance of establishing monitoring and evaluation systems, costing and economic modelling of intervention approaches, active engagement of a range of implementers and the target community, tailoring the scaled-up approach to the local context, the use of participatory approaches, the systematic use of evidence, infrastructure to support implementation, strong leadership and champions, political will, well defined scale-up strategy and strong advocacy.

Conclusions: Effective scaling up requires the systematic use of evidence, and it is essential that data from implementation monitoring is linked to decision making throughout the scaling up process. Conceptual frameworks can assist both policy makers and researchers to determine the type of research that is most useful at different stages of scaling up processes.

This journal club is a bit of a twist on the usual journal club posts that are about only one paper. I was looking into the literature on implementation and scaling of innovations, and noticed that these two review papers (one about factors for implementation, the other about factors for scaling) are interrelated. I considered separating them to write this journal club, but it would have lost something if I did.

The Durlak paper reviews the factors that affect implementation. Implementation could apply to the use of research findings and other outputs such as innovative products, interventions and/or services. The paper includes an ecological framework that outlines many of the key success factors for implementation. Milat reviews key success factors for scaling up after small scale implementation has been done. This could be for moving an innovation out of the lab and into a community setting as a pilot, or it could include scaling a pilot intervention either vertically (within similar organizations/contexts) or horizontally (more broadly in society). Milat’s review includes a table that synthesizes key components for scaling up based on various published models and frameworks.

I noticed that some people use “implementation” and “scaling” interchangeably, and while they are closely related their meanings are different.

Implementation is defined in Durlak (p.340) as “a complex developmental process that can be affected by a multiple array of interacting ecological factors present at the individual, organizational and community level”.

Scalability, is defined in Milat (p.2) as “the ability of a health intervention shown to be efficacious on a small scale and/or under controlled conditions to be expanded under real world conditions to reach a greater proportion of the eligible population, while retaining effectiveness” and scaling up is when these scalable interventions “are expanded under real world conditions into broader policy or practice…it involves explicit intent to expand the reach of an intervention to new settings or target groups and is accompanied by systematic strategy to achieve this objective”.

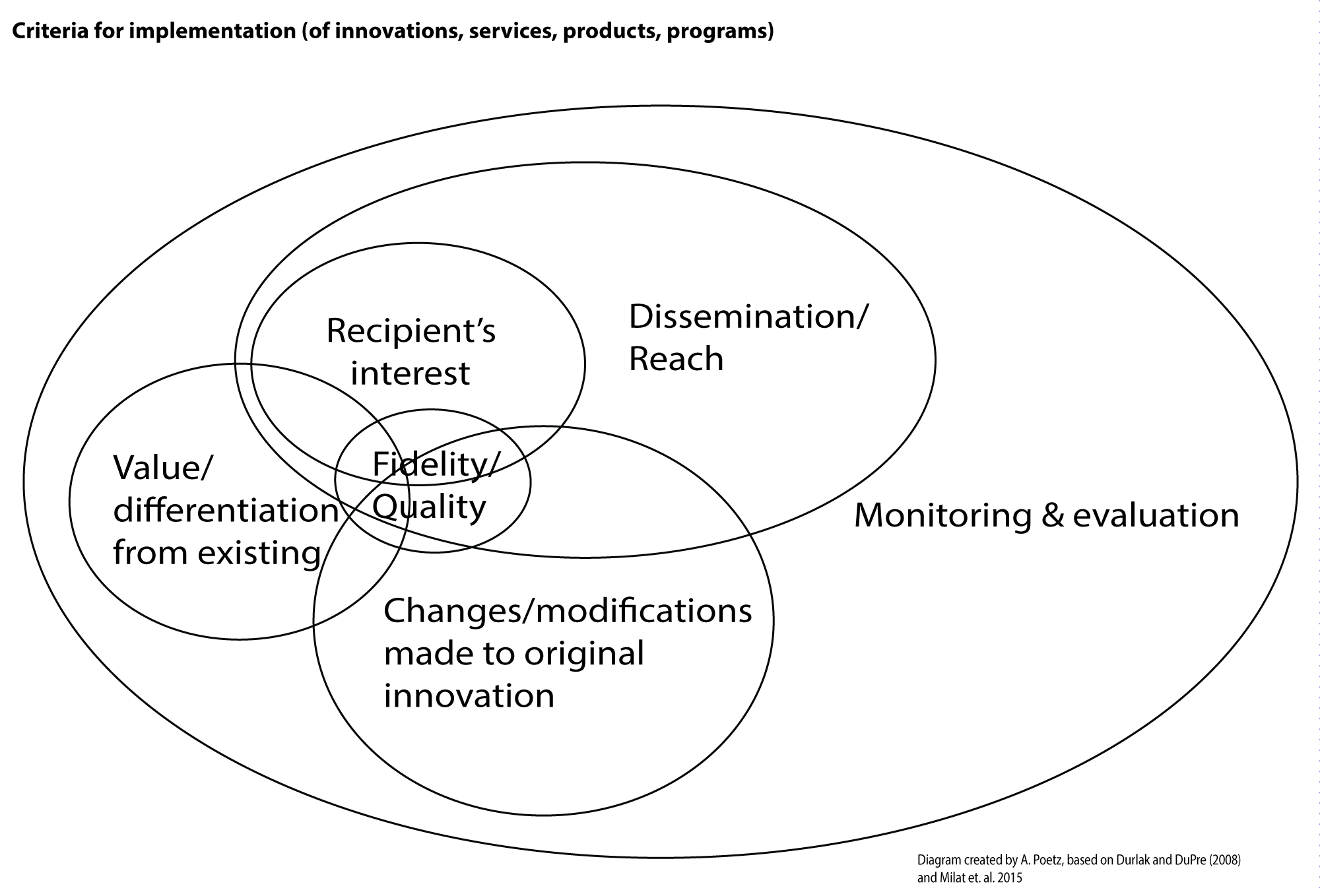

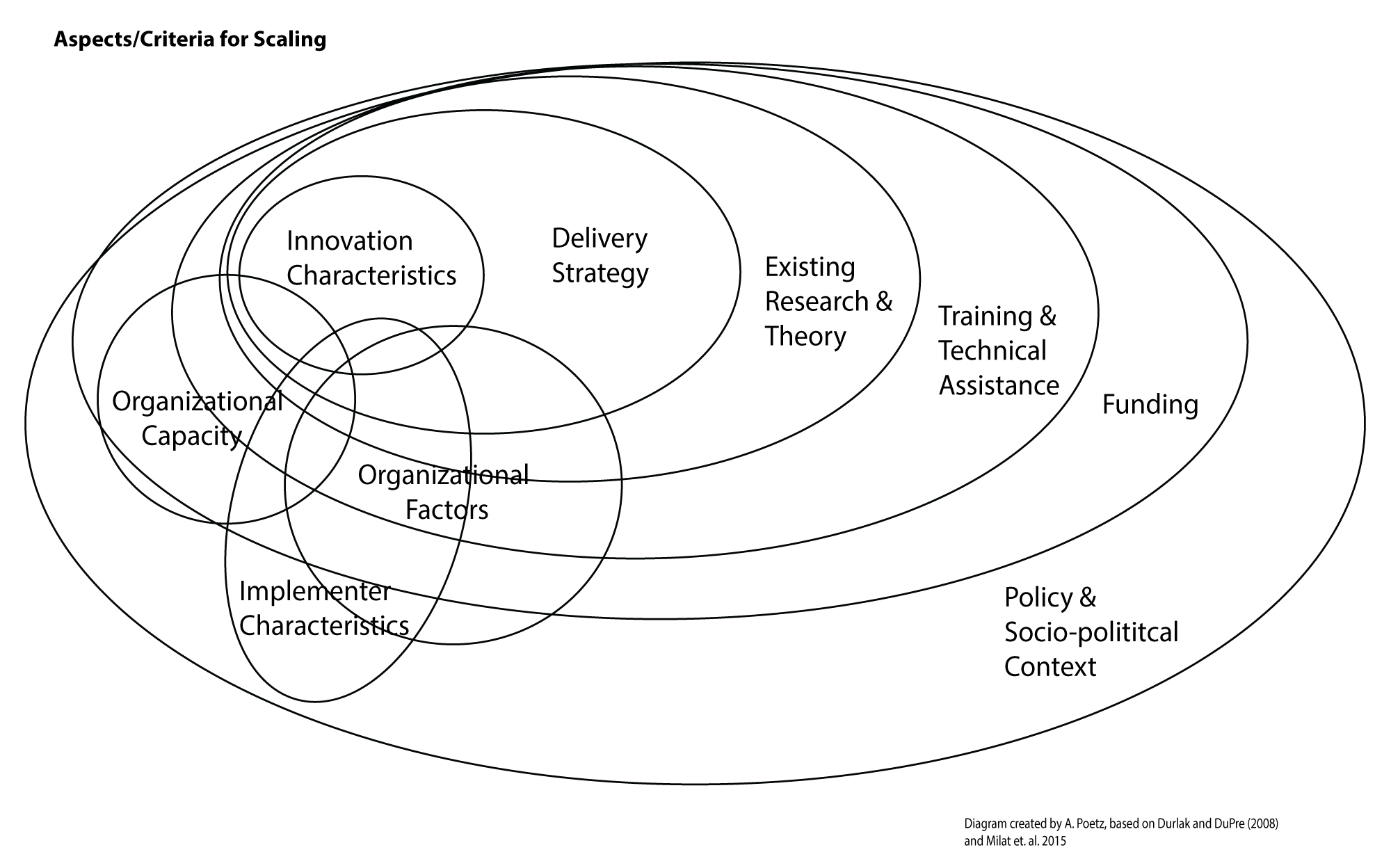

One of the authors points out that many tend to simplify the process of implementation and scaling in their minds, thinking that if they make an innovation available it will get used. I knew it was more complex than this but these articles helped me to see and articulate the fine details of the systems and sub-systems that are involved in the ‘ecology’ of implementation and scaling. The first thing I did after reading these papers side by side, was to put the key success factors for both implementation and scaling into a table, along with their respective meanings. Each paper used slightly different wording but often meant the same thing. As a social scientist, my mind automatically goes to seeing things like this in terms of the systems or interrelationships among the components, and I drew what I saw in my mind as I was reading these two papers. The diagrams I drew are below:

The diagram above shows that for implementation, the recipient’s interest in the innovation is key (if nobody wants it, it won’t be implemented), and is related to: the value it provides to them (how different is it from what already exists?), the changes or modifications made to make it work in their context, and their ability to achieve fidelity and/or deliver the service or intervention while maintaining a level of quality. The reach or awareness that can be gained about the innovation and whether it captures the interest of the intended recipients is related to the quality of the innovation, the value it provides and how adaptable it is to different contexts. Finally, qualitative and quantitative monitoring and evaluation needs to be done for all the factors: how far and wide is the innovation being disseminated so people know about it, is the dissemination strategy conveying information about the value the innovation provides, how well is the innovation being delivered (fidelity/quality), what changes were made to adapt it to a specific context and how is this affecting the fidelity/quality. This monitoring and evaluation can inform any scaling efforts if scaling becomes the next step.

In the diagram above, which depicts the systems/sub-systems or ‘ecology’ of scaling, the characteristics of the innovation are centrally related to all other factors. The innovation could be considered valuable by recipients, but still not used due to a variety of factors. These factors include the capacity of the organization such as the number of employees available, and implementer characteristics such as skill level of personnel within the organization who will deliver the intervention. Other organizational factors include political will/policies and leadership. All of these factors are influenced by the delivery strategy employed, research (on how effective the intervention is, and other existing research), quality and availability of training as well as ongoing technical assistance after initial training. These factors depend on available funding, which are often influenced by the current priorities of government and existing policies and legislation, as well as stakeholder priorities.

It is important to note that for each diagram, the size of the circles isn’t important, the key thing is how they overlap and interrelate to one another (affecting each factor either directly or indirectly). Each of these diagrams depict the complex systems within which implementation and scaling take place, and although not depicted visually, involve stakeholder engagement throughout to ensure usefulness, interest, and to inform ongoing monitoring and evaluation. Stakeholders (especially the implementers) who are engaged on an ongoing basis will ideally inform the necessary contextual adaptations (changes) to the innovation and delivery strategy, the content and aims of training and ongoing technical assistance, which will change their own skill level for delivering the innovation with fidelity/quality.

The two systems maps are related in the following way. First, both begin with stakeholder needs, in that, the central feature of “implementation” is the recipient’s interest, while the central criteria for scaling is “innovation characteristics”: each of these are (or should be) based on stakeholders’ needs. The ecology of implementation is also related to scaling because, implementation at any scale has to be accomplished before it can be scaled to another different context. However, implementing an innovation, even for the first time, is a form of scaling. So, the characteristics in each of the diagrams are closely interrelated. You may imagine, as I have, that the diagram representing the criteria for implementation fits into the diagram about scaling. What I mean is, all of the criteria for scaling are also important for implementation (regardless of the scale of the implementation) such as: organizational capacity, organizational factors, implementer characteristics, the training and technical assistance available, funding, and the socio-political context and existing policies.

These two diagrams may appear very complex, and indeed the processes for implementation and scaling are complex. The complexity arises from the number of interrelated factors, as well as the dynamic nature of systems as they change over time (which is why ongoing monitoring and evaluation is so important). However, reality further complicates these processes when you consider the readiness (or not) of interventions to be implemented beyond a lab setting, or scaled beyond a small community pilot trial, from the perspective of the researcher(s) behind the innovations. Another important point made in one of the articles is that sometimes researchers are reluctant to allow adaptations to an intervention or innovation, to enable its use in a different context. The recommendation was that researchers decide on what are the key characteristics of their innovation that cannot be changed, and then let go of control of the rest of the characteristics which will allow them to be adapted as necessary.

Questions for brokers:

1) Would you change anything about these diagrams? If so, what, and why?

2) What were your initial beliefs about implementation and scaling of innovations, and how did they change after reading this journal club?

3) Will you change the way you approach research, knowledge translation, and/or commercialization now that you know more about how complex and stakeholder-dependent implementation and scaling are? How?

ResearchImpact-RéseauImpactRecherche is producing this journal club series as a way to make the evidence and research on knowledge mobilization more accessible to knowledge brokers and to create on line discussion about research on knowledge mobilization. It is designed for knowledge brokers and other knowledge mobilization stakeholders. Read the open access articles. Then come back to this post and join the journal club by posting your comments.